Kai Pata

Problem types

Problems are commonly classified as well-structured and ill-structured problems (Simon, 1978): the former come with a familiar solution strategy and a single possible solution; for the latter, the strategy has yet to be developed based on what is known and there can be several solutions which are, depending on one’s perspective, approximately equal.

Another classification that is widely used distinguishes between simple and complex problems (Newell & Simon, 1972). Complex problems are novel; dynamic – the correct solution changes over time; solving them often depends on several factors unknown to the inquirer; complex problems generally have a multitude of solutions with approximately equal validity.

Thirdly, David H. Jonassen (2001) has tried to classify different kinds of problems in order to simplify the study of their solution models:

Simple problems include those with a single known solution and answer.

- logical problems –g.. solving the Rubik’s cube

- algorithmic problems – can be solved by applying a formula

- story problems – can be solved by applying a formula, but the task is presented in a narrative form and one needs to find out the parameters within the story before one can apply the formula.

- rule-using problems – rules (e.g. right hand grip rule in physics, linguistic rules, norms of behaviour, traffic rules) can be applied with a number of cases. Examples: grouping, creating a crossword, finding pairs, filling in the gaps.

Most workbook tasks are simple problems. For instance, the tasks in LearningApps environment are examples of simple problems.

Complex problems include those with several solutions and answers or those lacking a clear solution and answer.

- Decision making problems (see also: decision making);

- Troubleshooting problems;

- Diagnosis-solution problems (see also: case based learning);

- Strategic performance;

- Case analysis problems (see also: case based learning);

- Design problems;

- Dilemmas (see also: decision making).

Depending on the type of problem, it can be solved either in a task-based way (simple problems) or via an inquiry (complex problems). Problems that require an inquiry can be tackled in the form of project work and they are suitable for project-based learning.

Task-based learning scenarios for solving simple problems

Task-based learning is used most often during school classes. Usually, simple problems form some part of a lesson.

For task-based learning, choose a simple algorithmic, textual or rule-using problem. Simple problems have a single known solution.

Typically, solving a simple problem has four stages:

- preparing to create a solution, i.e. classifying the problem

- choosing or working out a solution strategy

- applying the chosen strategy to find a solution;

- evaluating the result that was generated.

Consider which digital tools could be used to support solving such problems. E.g. LearningApps and other similar environments for creating tasks are suitable here.

Creative Classroom task-based learning scenarios:

- Countable/uncountable nouns

- Reformation in Estonian lands

- “Werewolf”

- How many seeds we need?

- Studying the working principle of a dynamometer and gravity

- Sum of angles in a triangle. The exterior angle

- Reading poetry as an Avatar

- Changes in nature

- Adjectives

- Countable/Uncountable

- How to build a marshmallow catapult?

- Heroes and religion in Ancient Greece

- A task-based lesson in the framework of Code Week

Inquiry-based learning scenarios for solving complex problems

- Learning needs to be initiated by a problem.

- The problem has to promote constructive activities and knowledge that can be usefully applied in the future.

- Acquired knowledge will be integrated to the problem based on the problem rather than the subject.

- Students are directed to channel their activities (individually and collectively) in a way that contributes to solving the problem

- Various forms of group work (individually for the team, together for the team) rather than lectures are used.

Students are supplied with a general thematic framework within they can choose to explore the problems of their interest. Topics that connect with real life are emphasised. Problems are raised by the students themselves, who then set out to find solutions for them.

Complex problems are authentic (genuine, similar to the their original source). In task-based learning, problems that reflect actual situations are used. The way the problem is presented determines the activities that the students need to carry out to reach the solution (multitude of data, hard-to-find answers, multidisciplinarity, a variety of requisite skills). An authentic form of presentation ensures that learning takes place in a situation that resembles reality and renders the acquired knowledge and skills easily transferrable. To set up authentic problems, we should ask: who should care about the solution? The task is not authentic, if it has the sole purpose of producing a grade for the student. Authentic tasks contain problems that matter for the student. The text of an authentic task should reflect the roles of community members (politicians, parents, industry, population etc) – the social context of a problem is important. Solving an authentic problem should promote development of the community.

- The problem questions do not have obvious answers (finding the answer requires solving the problem in several stages)

- The problem questions are intriguing, important for the student/community (phrased in a way that is exciting and intelligible for the student).

- The problem questions are multifaceted (solutions require knowledge and skills from more than just one field)

- The problem questions depend on many different data (solutions involve data collection, analysis, interpretation)

Solving the problem with inquiry

The problem solving cycle can be set off inductively (by looking for patterns of regularities – in this case, it is not possible to put forth hypotheses immediately) or deductively (by putting forth hypotheses that are based on some theory, which will then be tested in the inquiry).

Inquiry-based learning leads the student to ask:

- What does the problem consist in?

- How would it be possible to solve the problem?

- What kind of solution or strategy should I attempt?

- How correct is my solution?

Inquiry-based learning scenarios often involve a model of inquiry with the following stages:

- What is the topic, the problem of your inquiry?

- Are you working alone or in a team to solve it?

- What do you know about the problem? (one could use e.g. mind maps)

- What kind of information could you collect to understand, clarify, explicate the problem?

- Form a plan of how to tackle the problem and share it with the teacher.

- Explore and observe – what kind of information is required, where can one find it, who is collecting it and how to involve others, where do I store the data, is it accessible to others, what forms of data am I collecting?

- Presenting the results – How do I present the results, who will be involved in interpreting the data and drawing conclusions?

- How do I organise a discussion to reach a better understanding of the results?

Some complex problems can be solved by following the stages of decision making. Making decisions comes up in the dilemma-type problems, for which there is no single correct solution or answer. Consequently, a multi-stage discussion is recommended for the decisions involved. For instance, one could carry out the decision making in the form of a role play or a simulation. See http://bio.edu.ee/envir/

In the course of solving a complex problem, the teacher and students integrate knowledge and skills from several subjects. Activities are organised in a way that supports reaching a solution. The goal of problem-based learning is to find a comprehensive solution in a prearranged format (e.g. research paper, chart, action plan).

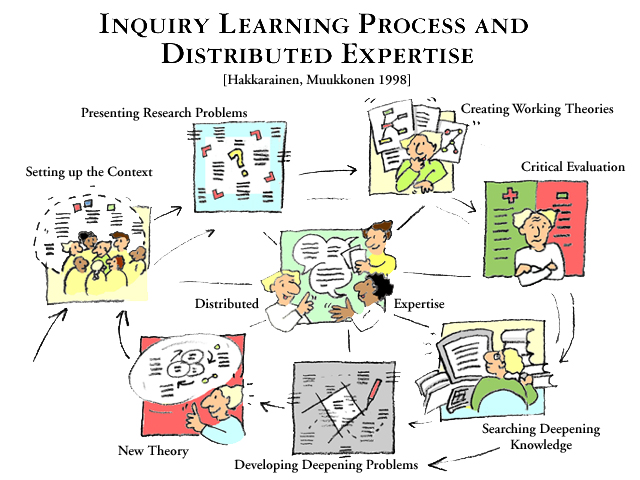

Progressive inquiry phases

Progressive inquiry is a pedagogical model of inquiry-based learning, where learning is subjected to the same methodology as scientific research.

Inquiry-based learning is founded on the principle that the learner does not merely generate new knowledge, but this knowledge is integrated with pre-existing knowledge in the context of solving problems, in the course of which one’s own explanations and theories are developed. The new knowledge does not support the learning of merely an individual, but the whole group involved in the process.

The process of inquiry-based learning kicks off from a problem situation or context based on which the student:

- presents the context

- formulates a research problem – raises important questions

- finds the relevant information sources for tackling the questions, seeks for deeper knowledge

- puts forth a working theory and provides critical evaluation – presents his/her own vision for others to analyse and analyses the ideas of others

- offers solutions of one’s own based on the analysis

- conducts an in-depth investigation of the problem – carries out the necessary studies

- creates a new theory

- shares one’s expertise (participates in constructive group discussion)

The main role for the teacher in inquiry-based learning is to guide the students toward asking important questions based on a given context and to encourage them to propose their own theories. In practice, this means that results will be reached through collaboration and independent analysis, using additional sources of information when needed.

Creative Classroom inquiry-based learning scenarios

- Indrek Hargla’s historical crime fiction series about Melchior the Apothecary

- Discrimination

- Geometric shapes around the schoolhouse

- Properties of the graphs of linear functions

- Finding solutions to environmental problems

- Outdoor learning for 5th-6th grade nature education. Determining air quality by using lichen